A recent development in Haskell land is the formation of the GHC DevOps Group, which was the topic of last week’s blog post. The group is a community of parties committed to the future of GHC. Tweag I/O is one such party. We are helping the group achieve its goals with concrete engine room work. We presented some of our plans at the Haskell Implementor’s Workshop, but here’s a post for those who weren’t there. (We also made the presentation slides available.)

GHC release quality

GHC’s past release schedule and release quality has varied. In fact, in our sample of users and clients, many dread major GHC releases.

While the GHC DevOps Group has already committed to improve the continuous integration setup, automatically running tests at every new commit is practice that has been in place for some time. This means running the GHC regression testsuite by way of the ./validate script for every commit and for every pull request or differential. However, major GHC releases have in the past shipped with serious bugs that passed GHC’s own regression tests and only manifested in third party packages. Given GHC’s enormous surface area, this is not particularly surprising. Consequently, the integration of testing against third party packages into GHC’s development process appears to be a logical step to improve release quality.

Third party challenges

While conceptually attractive, the addition of third party packages to regression testing comes with its own set of challenges. Firstly, changes in GHC or core library behaviour or simple alterations of core package versions break some third party packages. This is compounded by package dependencies when a package that many others depend on breaks. Secondly, package authors or maintainers may not be willing or able to immediately respond to changes in GHC and its core libraries, but at the same time, package maintenance shouldn’t be offloaded onto the already very busy GHC developers. Thirdly, some packages are more important to the ecosystem and the GHC user base than others; we would like to focus our scarce resources on those packages that matter the most.

But we are all fortunate to have in the Haskell community a uniquely valuable asset that few other languages have developed to the same scale: Stackage, a huge curated set of Haskell packages that have been painstakingly tested to work together and whose respective maintainers have agreed to keep packages updated in a timely manner. Combined with the popularity of Stackage among developers, this ensures a representative set of the most widely used and best maintained packages in the Haskell ecosystem. Hence, it is the perfect package candidate set for regression testing.

From Stackage Nightly to Stackage HEAD

Stackage currently builds package sets in two flavours: nightlies and LTS (long term support) sets. The nightly set is based on the most recent package versions from Hackage for the latest release version of GHC, whereas LTS sets are versioned and maintain stable interfaces by only occasionally updating package versions beyond patch updates. For the purposes of regression testing the current development version of GHC, the nightly flavour of Stackage is the appropriate starting point, as it continuously tracks package updates by package maintainers.

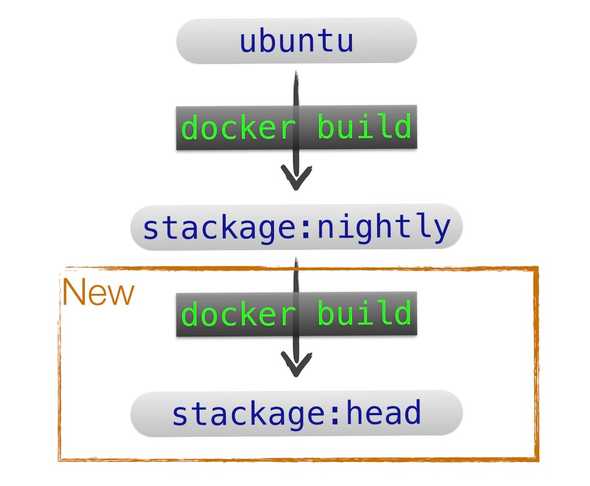

Building of so called Stackage snapshots is a two-phase process. First, a Docker image called stackage:nightly, containing the appropriate version of GHC and the rest of the Haskell toolchain in combination with all C libraries and other non-Haskell dependencies for the package set is being build on Travis CI. Second, a tool called stackage-curator builds the Haskell packages that are part of the package set inside a Docker container running stackage:nightly.

To perform regression testing of GHC HEAD, we need to alter both steps. Firstly, we use stackage:nightly as the basis for a Docker image that contains all the same non-Haskell dependencies, but includes the latest development version of GHC. We call it stackage:head. This is illustrated in the below diagram.

Pruning constraints

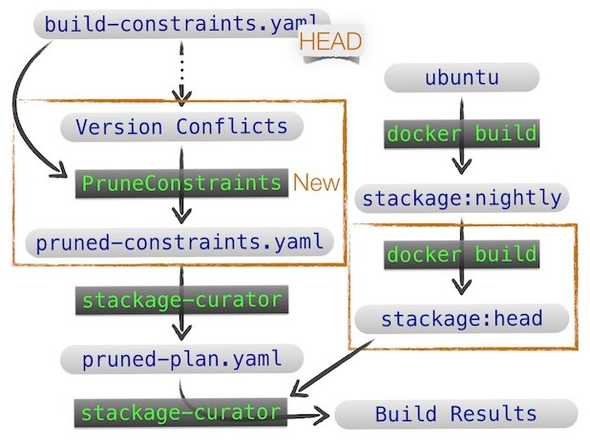

The second step in the Stackage build process, based on stackage-curator, is itself a two-phase process. First, stackage-curator converts a specification of build constraints into a concrete build plan. These build constraints are manually maintained by a group of people known as the Stackage curators. Secondly, stackage-curator (the tool) executes the build plan by building all packages in the package set.

However, not every generated build plan can be executed. In case of package version conflicts, we may get an invalid plan. When using the latest development version of GHC, the HEAD, in combination with the build constraints of Stackage Nightly (which is curated to work with the latest stable release version of GHC), we invariably get an invalid plan. As we want regression testing to be a fully automatic process, we don’t want any manual intervention in the form of manually curating a set of build constraints specifically for GHC HEAD. Instead, we use a small Haskell script that prunes the build constraints by simply removing all packages that participate in a conflict. We call the resulting set of build constraints the pruned build constraints. They are then used to build packages. That build process may fail for individual packages if there is a regression or a conscious change in GHC. Overall, we get the following architecture.

Assessing changes to GHC

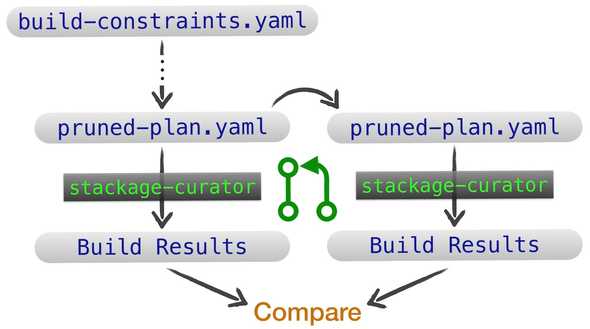

One of the interesting questions that we want to answer with the HEAD build of Stackage is whether a change to GHC involves a regression. Given that a HEAD build will typically involve failing packages and package failure may have a variety of reasons, it seems difficult to make that determination.

However, a change to GHC is always a change with respect to a particular earlier version of GHC HEAD — this may be in the form of a pull request or a differential. Hence, what we are actually interested in is the change in package failures between two only slightly different versions of GHC. Any package whose build fails for both versions can simply be ignored. In contrast, whenever a pull request or differential leads to a new package failure, we have got a situation, where a code reviewer or code author needs to assess whether the failure is acceptable (GHC’s behaviour or core library APIs underwent a planned change) or whether it indicates a regression.

Collaboration

Adding a new Stackage flavour tracking GHC HEAD buys us,

- that GHC developers can identify upfront which packages are affected by planned changes to GHC and the core libraries,

- and that package maintainers are given plenty of advance notice about those changes that do break backwards compatibility (because say packages were relying on buggy behaviour by the compiler). Ultimately, this scheme empowers package developers to adapt to those changes early, or at any rate, to get a longer lead time to plan and schedule the work involved.

- Quantify just how many current Stackage packages (and by proxy the entire ecosystem at large) are ready for the next GHC release, and track that number over time.

In short, this new Stackage flavour should prove useful for both GHC developers upstream, and library maintainers downstream. Better yet, regression testing against all of Stackage has the potential to allow a closer collaboration between GHC developers and package authors. New versions of previously breaking packages on Hackage get picked for regression testing automatically once builds and tests start succeeding.

Behind the scenes

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.