Every day we write repetitive code. A lot of it is boilerplate that you write only to satisfy your compiler/interpreter: code that is not related to the main logic of the program like import and export lists, language extensions, file headers. But how do languages differ in their boilerplate content? Is it only the content of the boilerplate that changes, or also its quantity? We explore these questions using data sets of Python and Haskell code. Besides satisfying our curiosity, we will learn about community-wide habits and realize that after all, repetition is not necessarily uninteresting!

A first look at the data

Our data sets come from public repositories of Haskell and Python packages. In the case of Haskell, we use a current snapshot of all packages on the Stackage server. For Python, we downloaded a random subset of approximately 2% of all packages on the Python Package Index. Based on our sample, we estimate the total size of all (compressed!) packages on PyPI to be approximately 19 Gb. We chose to use only a small sample from PyPI so that we could perform analyses on our laptops. This sampling allows us to load the Python data set in memory, while keeping its size comparable to the Haskell one.

Let’s first look at a few key characteristics of our data sets, namely the number of packages, total number of lines of code (LOC), LOC per package, number of words, and the most common word:

| Python | Haskell | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of packages | 3414 | 2312 |

| LOC | 6,048,755 | 3,862,107 |

| Average LOC per package | 1772 | 1760 |

| Number of words | 36,577,867 | 23,174,821 |

| Most common word | x (6,7%) |

NUL (4,5%) |

Hold on! NUL is the most common word in Stackage packages? Surprising, but true: \NUL is the quotation of the null character, and a small number of packages (2.7%) have inline byte strings with many, many copies of \NUL in them.

The next common Haskell word is “a”, which is a common type and term variable name.

It is also interesting to see that the average number of lines of code is very, very similar in the Haskell and the Python data sets!

Import statements and language extensions—how many are there?

Now let’s take a closer look and see what we can learn from this data.

As you might know, in both Python and Haskell files start with a list of import statements. In Haskell, file headers also contain a list of LANGUAGE pragmas, which add extensions to the language.

We thus expect import statements to be a common pattern in the source code data sets.

In Haskell, we imagine LANGUAGE pragmas to be another common pattern.

Let’s find out whether there are any differences in the frequency of these patterns between Python and Haskell code.

We can easily determine a package’s fraction of lines of code that correspond to import statements and LANGUAGE pragmas:

this fraction is just the number of lines of code with import and language pragma keywords divided by the number of all lines of code.

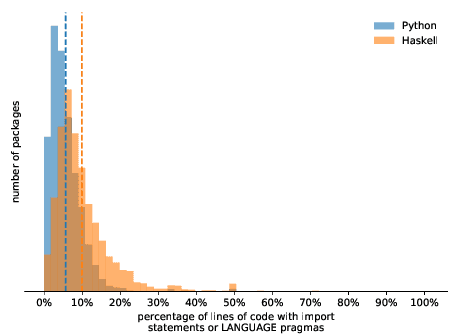

The following histograms show the results:

Haskell tends to have more import and LANGUAGE statements per package than Python, as indicated by the average percentage (dashed lines):

for Python, it’s about 6%, while for Haskell it’s about 9.5%.

Interestingly, in both languages, a few packages have a very high fraction of this specific kind of boilerplate code.

Those can be found from the 50% mark on but they are not visible in the figure because of their low package count.

In case of Python, such packages often are setuptools scripts, while for Haskell, they are module exports and setup files.

… and which are the most frequently used?

Answering this question amounts to extracting the name of the imported package or used LANGUAGE pragma for each line of code.

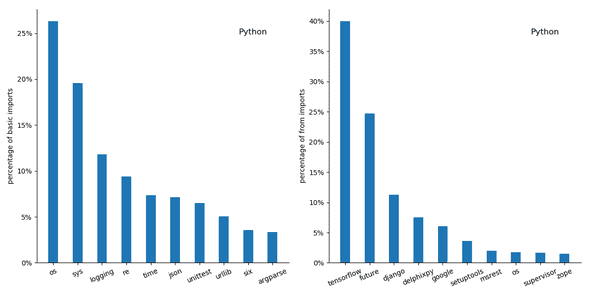

For Python, we first look at basic import [...] statements:

Few surprises for Python’s basic imports - os and sys are the most frequently imported modules.

In fact, they make up 27% and 19% of all basic imports.

But things change dramatically when considering from [...] import [...] statements:

40% of all from [...] import [...] statements import things from TensorFlow, a popular machine learning library.

We know that TensorFlow is popular, but that popular?

It turns out that our random sample of Python packages happens to contain a complete version of TensorFlow and that “self-imports” within that package account for 83% of all TensorFlow imports.

It is thus a single, big package which leads to this surprisingly high percentage of TensorFlow imports.

Disregarding that package, around 2.5% of all import statements are concerned with TensorFlow, which would still crack the top 10.

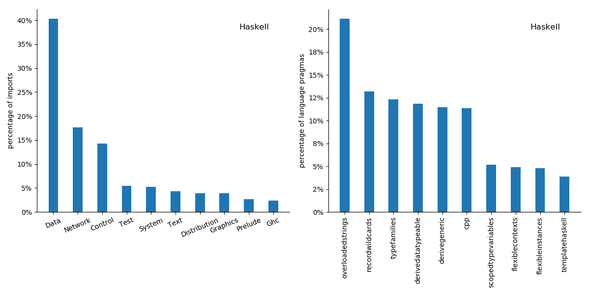

Onwards to Haskell:

Here we find an unexpectedly high occurrence of explicit Prelude imports. Imports from the Data namespace make up 34% of all import statements, which matches our intuition that its contents are very frequently used.

When considering the most frequently used language pragmas, perhaps unsurprisingly, the OverloadedStrings extension leads the field:

40% of all Haskell packages in our data set use this extension.

The popularity of this extension makes a good case for OverloadedStrings to enter the Haskell standard.

Furthermore, it’s surprising that TypeFamilies is the third most common language pragma. Type families are a fairly advanced subject and one would thus expect them not to be that commonly used.

We can also compare our results to a previous analysis of Haskell source on GitHub, which, too, finds that OverloadedStrings is the most popular extension.

The ten most popular extensions listed in the figure above also feature in that analysis’ list of the 20 most frequently used language extensions, although not necessarily in the same order.

The reason for that is not immediately clear—it might be that our Haskell data set is not representative of all Haskell code on GitHub; after all, at the time of writing, there are around 45,000 Haskell projects on GitHub, while our data set contains only 2,312 packages.

Conclusion

We took a first look at our data sets and investigated import statements and LANGUAGE pragmas in Python and Haskell.

By filtering code lines for certain keywords we were able to answer interesting questions about the frequency with which these basic coding patterns occur and how their frequency differs between Python and Haskell code.

But our data sets have potential for much deeper analysis of less obvious patterns.

A pattern can be characterized by a set of similar lines of code, and we expect to find, for example, control structure patterns such as for loops.

But are there unknown patterns to be discovered that we didn’t think of?

How do we discover them in our data sets?

How do they differ between programming languages?

And can we somehow exploit these patterns—think code completion or tools such as presented here?

We’re excited to see what other insights these data have to offer—stay tuned!

Behind the scenes

Simeon is a theoretical physicist who has undergone several transformations. A journey through Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, computational structural biology, a wet lab and renowned research institutions in Germany, Paris and New York finally led him back to Paris and to Tweag, where he is currently leading projects for a major pharma company. During pre-meeting smalltalk, ask him about rock climbing, Argentinian tango or playing the piano!

Matthias is a scientist and developer who worked at Tweag. He says he's a generalist "half scientist, half musician, and a third half of other things" but you'll have to ask him what that means exactly! He lives in Paris, and enjoys a good discussion, writing long-form texts in vim or reading and occasionally writing code.

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.