I got the opportunity to work on Asterius, a new Haskell to WebAssembly compiler, during my internship at Tweag. My task was to get

anything numerics-related stabilized in its compiled code. Generally, this meant experimenting with all

the conversion routines between Float, Double, Rational, Int,

and the ton of intrinsics that the Glasgow Haskell Compiler (GHC) provides for these values.

TLDR I helped integrate a part of GHC’s test suite with Asterius during my internship at Tweag. Now, it can pass almost all of the

numerics test suite. It was a really fun experience—I got to read a bunch

of GHC sources, fight with the garbage collector, and come out knowing a lot

more than I did when I went in. We also ended up making some modest contributions

upstream, to binaryen,

tasty,

and GHC.

First steps: getting up to speed · PR #114

I spent my first week getting familiar with the Asterius codebase so I could fix a bug

with coercion from Int64/Int32 values to Int8 values. This task forced me to explore both

the Asterius codebase and the corresponding GHC sources that

were responsible for this bug. I continued making other small, localized

fixes that enabled me to get to know the rest of the codebase.

Integrating the GHC test suite · PR #132

The next major thing we worked on was integrating a part of the GHC test suite

into Asterius—to enable us to sanity check our runtime against GHC’s

battle-hardened test suite. The original GHC test suite is a large Python and

Makefile based project which needs significant work to reuse for Asterius,

so we chose an alternative approach: copy the single-module

should-run tests into our source tree, write a custom tasty driver to run

each test, compare against expected output, and write results into a CSV report.

The CSV reports are available as CI artifacts, so by diffing against the reports

of previous commits, regressions can be quickly observed.

The initial numbers were interesting: of all 706 tests integrated so far, if we were optimists, then 380 were passing, which was about half of all tests. And if we were pessimists…

We rolled up our sleeves and got to work: I decided that by the end of the three months, I

wanted all tests in the numerics/ subfolder stabilized. These tests mostly deal with

everything related to numbers including conversions between Float, Double, Rational, Int, Word,

the various intrinsics in GHC.Prim for numbers,

and tests for Integer support (implemented in Asterius with JavaScript BigInts).

Stabilizing numerics

The workflow to crush a bug was essentially:

- Pick a failing test case that looks like a low-hanging fruit

- Read the relevant GHC sources

- Pin down what’s going wrong by repeatedly shrinking and logging

- Fix it, ensure the test case turns green

- Goto step 1

It sounds quite repetitive, but it was anything but. I learned a lot of interesting details about GHC’s internals. For example, some of the ones I remember fondly are:

- The printing of

Floatvalues is based on a paper: Printing Floating-Point Numbers Quickly and Accurately - One can run GHC inside GDB to debug GHC’s debug DWARF output

- GHC FFI crashes on C’s varargs

- GHC hangs on compiling large exponents

- The implementation of

mfixforIOuses anMVar - The implementation of

cartesianProductfromData.Setis derived from an implementation written by Edward Kmett, with a statement about the optimality of the algorithm: “TODO: try to prove or refute it.”

At the end of all of this, I had in total 59 PRs, 40 of which got merged into Asterius. The rest are either closed experimental branches, or open PRs waiting to be merged.

Our failure rate on GHC test suite has changed as:

- Then:

327/707failures in total,36/50failures innumerics(collected from commit6290d24) - Now:

168/707failures in total,3/50failures innumerics(collected from commit222858b)

Most of the remaining bugs we categorized appear to fall into the following classes:

- A lack of runtime features like multi-threading, STM, etc.

- A lack of full Unicode support

- Subtle issues in various parts of the runtime, e.g., the storage manager

Aside: GC bug hunting

Eventually, we found ourselves running into bugs in our implementation of the garbage collector in Asterius. These are usually incredibly painful to debug. Two major sources of the pain are:

- When the GC malfunctions, the heap is already in an inconsistent state, however, the final crash site can be quite far away. All we’re left with is the final error message of the crash. We need to work backwards for a long time to locate the crime scene; worse, it’s not even always obvious that the root cause of the bug lies in GC, judging from a seemingly irrelevant error message.

- The WebAssembly platform still lacks a good debugging story. Well-established

tools like

gdbaren’t available; we don’t even have standardized DWARF sections yet! The plain old logging approach is still the central way of hunting bugs, if not only.

Other than the seemingly endless loop of adding more logging logic and rerunning

tests, we do have some debugging-related infrastructure. Since Asterius is a

whole program compiler on the Cmm level, it’s possible to implement aggressive

link-time rewriting passes to add tracing or asserting logic. For example, we

implement the “memory trap” feature when the debugging mode is enabled: it

replaces all wasm load/store instructions with calls to our read/write barrier

functions implemented in JavaScript. These functions utilize the information in

the block allocator and check whether an address points to a region which is

already recycled by the copying GC. The memory trap is quite useful in making

GC-related bugs crash as early as possible, and we indeed spotted use-after-free

bugs with its help.

Another approach to check whether a runtime bug is GC-related: not running GC at all! We implemented a “YOLO mode” in the runtime which disables all evacuating/scavenging logic, and the only thing GC does is allocating new space for the nursery and resuming Haskell execution. By running the test suite with/without the YOLO flag and diffing the reports, we can quickly tell whether a test failure is likely related to GC.

I also eventually ended up writing helpers to structure the heap and figure out what

arbitrary bit patterns I was looking at—bollu/biter

was written during an afternoon of debugging some messed up floating-point representation bug

caused by incorrect bit manipulation.

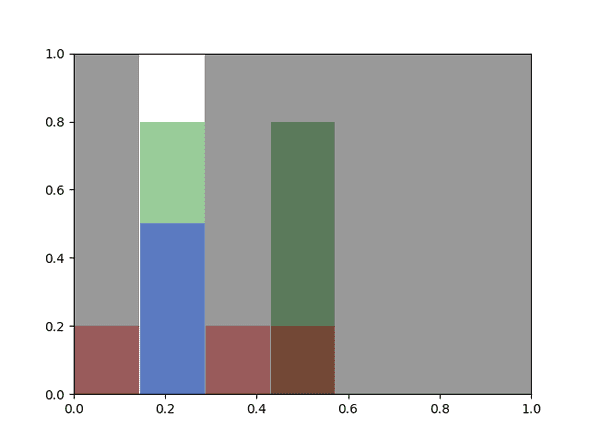

Similarly, another technique I began using was to create debug logs that would emit Python code. This Python code would then render the state of the heap at that given point in time: this is a much saner way to see what’s going on than view raw numbers or bit strings. For example:

The fact that the gray region overlaps with the green region is a Bad Thing since we were freeing up some memory that is actually still kept alive by the higher-level heap allocator. Without visualization, this sort of thing is tough to recognize when you’re staring at nothing but pointers which look like:

9007160601084160, 9007160602132736, 9007160603181312, 9007160604229888, 9007160601084160...So, the root cause of the bug above was some missing synchronization logic

between our two levels of allocators. We have a low-level block allocator which

allocates and frees large blocks of memory, growing the wasm linear memory when

needed; above that comes the heap allocator which keeps a pool of blocks to

serve as nurseries of Haskell heap objects. After a round of GC, we have a set

of “live” blocks which make up the “to-space” of copying GC, and we free all

memory outside the set. But we should have also been keeping alive the blocks

in the pools owned by the heap allocator; otherwise a piece of already “freed”

memory can be provided as nurseries without proper initialization. Look at

the Python-generated graph, and the simple yet deadly problem is made obvious.

In general, debugging the GC took lots of patience and code. There are entire branches worth of history

spent debugging, that did not get merged into master.

Wrapping up

I loved working on Asterius at Tweag! I got to contribute

stuff upstream, got my hands dirty with the garbage collector, the low-level cbits (C functions for various standard libraries), and

while helping a real-world project! I hope to continue working on this and get the number of

bugs down to zero.

Finally, Tweag’s Paris office is a fun place to work! I picked up (very little) French, a bunch about sampling and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques, tidbits of category theory and type theory, some differential geometry, and enjoyed lunch conversations about topics ranging from physics to history. It was a delightful, rewarding experience—both personally and professionally!

Behind the scenes

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.