This post is about compiling refinement types into a dependently typed core language, my project as an Open Source Fellow for Tweag. The post assumes some passing familiarity with the concept of dependent types, and little else. By reading this post, you will learn what a refinement type is, and how we might implement a refinement type system (like Liquid Haskell) on top of a dependently typed language (like Idris, or, more tantalizingly, what Haskell might soon become), by translating refinement types into dependent pairs (also called existential types or Sigma-types). You will also get a glimpse of what an Open Source Fellow can accomplish during their time at Tweag. Completing this project — translating refinement types to dependent types — was the goal of my fellowship.

Introducing refinement types

A refinement type (RT) is a regular type (like Int), endowed with some

predicate restricting the set of admissible values. As an example, { n : Int | n > 5 } is an RT describing the set of integers that are greater than 5.

Refinement type systems are designed to enable machine-decidable proof

finding. A programmer can write

addPos : { a : Int | a > 0 } -> { b : Int | b > 0 } -> { n : Int | n > a & n > b }

addPos a b = a + band, if the RT system accepts this definition, be sure that its runtime

behavior is as specified: the result is greater than both inputs. This

checking can often be completed by an SMT

solver, a

separate tool adept at proving or disproving logical statements. In this case,

the type-checker might ask the SMT solver to check whether

∀ a : Int. ∀ b : Int. (a > 0 ⋀ b > 0) ⇒ (a + b > a ⋀ a + b > b) holds.

One way to understand a refinement type { x : A | P x } is to see it

as a type of pairs of a value v of type A, together with a proof of P v.

In a dependently typed system — where we

can encode logical predicates with ease — this construct is called a dependent

pair, or a Σ-type. Note that

the predicate references the associated value; in other words, the second

component of the pair depends on the first one.

The Liquid Haskell project is about adding easy-to-use refinement types to Haskell, and its pages contain many great examples and a way to interactively experiment with refinement types.

Unifying refinement and dependent types

This understanding raises a natural question: if refinement types are a subset

of dependent types, can we compile the former to the latter? Doing so would

allow us to add the ease of programming with refinement types on top of existing

dependently typed languages. Refinement type

systems can be complex and be difficult to type-check, often requiring a notion of sub-typing (because, for

example, all values of type { n : Int | n > 1 } are also values of type { n : Int | n > 0 }). Dependently typed systems, on

the other hand, do not generally have sub-typing and can be designed to be

easy to type-check.

In order to tackle this problem methodically, I first made the problem concrete, by writing a compiler that translates a small source language into Idris source code. My source language is based on the first paper describing liquid types (that is, decidable refinement types) for OCaml.

As an example, given a definition in my source language:

relu : (x : Int) -> { v : Int | v >= 0 & v >= x }

relu x = if x > 0 then x else 0my compiler produces:

relu : (x : Int) -> (v : Int ** ((v >= 0) = True, (v >= x) = True))

relu x = MkDPair {P = \v => ((v >= 0) = True, (v >= x) = True)}

(if (x > 0) then x else 0)

elided_proofWe see here that the output relu produces a dependent pair (the ** is

Idris’ syntax for dependent pairs) that follows closely the refinements

specified in the input relu. The elided_proof is actually part of the

output: we are not yet concerned with converting the actual SMT-provided proof

into Idris, so we just trust the solver and erase its proof.

I soon started hitting the limitations of the type system described in the paper mentioned above. Critically, that paper does not support function application in refinements. Yet consider this example:

f : (x : Int) -> { v : Int | v > x }

g : Int -> Int

h : Int -> Int

h y = f (g y)In this case, to type check the body of h, the x in f’s type gets

substituted by g y, so the return type is { v : Int | v > g y }, but the

refinement language cannot express this type! So I just extended the source

language to support refinements with arbitrary terms, also bringing it much

closer to what dependently typed languages can express.

Formalizing the translation

This was perhaps two or three weeks into the Fellowship, when my Tweag mentor, Richard Eisenberg, and I started discussing what should be the final deliverable of the 12 weeks. There were two options of bringing this to fruition:

-

I could take my experience with the toy prototype and do something like Liquid Haskell, but for Idris.

-

I could also work on a research paper capturing this idea of compiling refinement types into dependent types. But what would the main proof in the paper be?

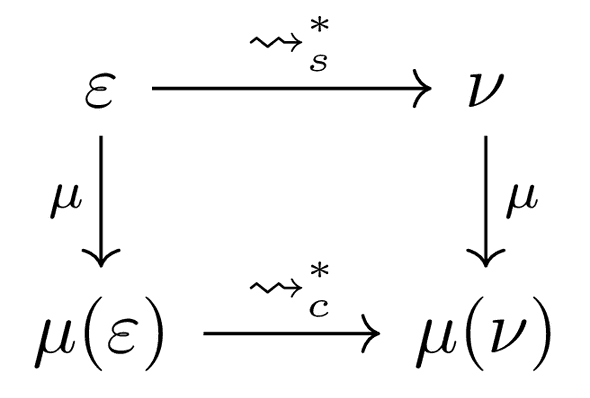

At this moment, I decided with Richard to establish a theoretical foundation to what I am doing, and work on a research paper formalizing that. This paper would be the deliverable for my fellowship. The weekly calls with Richard became way more substantial. First, we agreed to start writing the paper from its guts, describing some surface language (essentially, the simply-typed lambda calculus with refinements), some core dependently typed language (Calculus of Constructions looked like the right candidate) and defining a translation from the former to the latter. It also became obvious what needs to be proven: ultimately, the translation μ is correct if any well-typed surface language term ε translates into a well-typed core language term μ(ε) and if translation “commutes” with the languages’ operational semantics, as shown in this diagram:

Richard soon suggested to abstract away the notion of an SMT, replacing it with a black-box oracle. This abstraction was very fruitful in both the implementation (I separated query generation from solving, bringing a fair share of insights) and the paper (allowing a focus on what matters for my specific work).

With that abstraction, writing the paper was pretty straightforward at first:

I just needed to formalize the syntax and the typing rules. However, the paper

started to deviate from the implementation more and more. For instance, the

initial surface language from the paper supported booleans and

if-then-else, but it wasn’t

obvious how to expand all that to arbitrary algebraic data types (ADTs), especially

having constructors with data members (as opposed to an enumeration like data Bool = True | False). I thus added ADTs in the language, and I needed

pattern matching sufficiently expressive to enable proofs in the case branches

to depend on the choice of branch, a property called path sensitivity.

Path sensitivity implies that each case branch needs to remember the

relationship between the scrutinee and the variables introduced by the branch

pattern. In other words, if there is case s of Con x1 x2 ... -> ... then

there should be a proof that s = Con x1 x2 ... available on the right-hand

side of the pattern. Expressing this in the classical dependently typed

language formulation turned out to be quite difficult, so Richard and I

accordingly decided to add all the required machinery to the core language.

The paper is not yet finished, though, but it’s quite close to completion, with several key results already proved. Beyond that paper, I also plan to get back to coding and complete something like Liquid Idris, fulfilling the first option for the project I mentioned above.

The experience

Beyond just the technical work above, it may be helpful to readers to learn about my experience as an Open Source Fellow.

Firstly, all the conversations with Richard would be meaningful even if they only helped the project to go forward. But I’d like to emphasize the importance of observing how somebody else thinks, analyzes, what questions they ask, and so on. It’s like learning how others learn, and learning not just specific answers but also figuring out how they arrived at those answers (and any questions, which are equally important). It’s way more important in the long run.

Secondly, even building the type systems for some specific goal, let alone formulating and proving all those theorems, turned out to be an enlightening experience. Of course, “learning by doing” is a well-known concept. Still, even then, one thing is to follow somebody else’s exposition of existing theory and learn by doing, say, exercises in a book, but trying to come up with something of one’s own that makes sense is entirely different. That’s when it becomes clear why specific theories are built the way there are. Making one’s own little theory is an existential experience!

And, finally, sometimes the exciting problems are lurking somewhere where you least expect to encounter them. For example, that question of encoding ADTs to allow dependent pattern matching proved to be one of the most challenging problems I faced while working on this project. Of course, I made a mental note to get back to it once I complete this project, yet I stumbled upon that question almost by chance.

Conclusion

All in all, this Fellowship was a very enlightening experience. I had lots of fun working on the original toy language implementation and trying to formalize what I’ve done with pen and paper and discuss all of that with Richard.