Tweag is happy to announce the public beta release of a major internal project: a web service called Chainsail that facilitates sampling multimodal probability distributions. It is an effort to expand the applicability of Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling (MCMC), modern probabilistic programming tools — and, by extension, Bayesian inference — to more complex statistical problems. Tweag provides the computing resources required by Chainsail (within reasonable limits) free of charge.

If you’re impatient, you can skip right to our walkthrough video where we demonstrate briefly what Chainsail does and how to use it. But if you prefer reading what Chainsail is about in more detail, please be seated while we briefly taxi you through an introduction of Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling, multimodal distributions, and why they are difficult to sample, before we take off for a walkthrough of Chainsail and finally land with some final remarks.

Sampling multimodal distributions

Sampling from probability distributions is a ubiquitous, but often difficult undertaking:

every time you try to represent a population of things by only a few members, you are sampling, and you want to have representative samples to make confident guesses about what the whole population is up to.

In more formal terms: you draw representative samples to approximate an unknown (probability) distribution, and the “representative” is where things get difficult.

Defining complex probability distributions, especially for application in Bayesian inference, and sampling from them, has become much, much easier and user-friendly in the last few years thanks to probabilistic programming libraries (PPLs) such as PyMC 3 or Stan.

These PPLs allow you to define a statistical model programmatically in general-purpose or domain-specific languages and provide a range of methods to sample the model’s probability distributions.

Sampling is most commonly performed using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, which are iterative algorithms that build a Markov chain by starting from an initial state, proposing a new state depending on the current state and accepting or rejecting it, depending on the old and the new state’s probability.

This method works great for distributions that have a single mode, meaning, only one region with high probability.

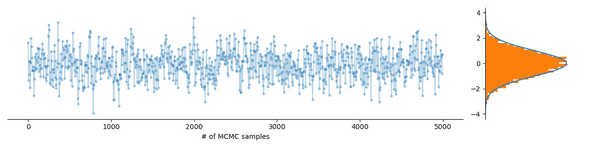

The following figure shows a Markov chain effortlessly exploring such a unimodal distribution:

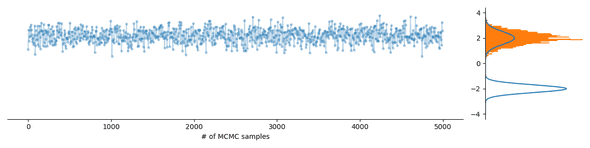

All great, but what if you want to sample a multimodal probability distribution, meaning, it has several regions of high probability, such as the Gaussian mixture distribution occuring in the soft k-means clustering method, when you have an identifiability problem or when you have ambiguous data? What then often happens is that the Markov chain exploring the probability distribution gets stuck in a mode, as demonstrated in the following figure:

This means that the samples you draw might not be representative of the full distribution and as a consequence you might be missing out on important new information, like an alternative cluster assignment or an interesting biomolecular structure. Some PPLs implement algorithms that help deal with multimodality, such as adaptive path sampling and stacking in Stan, but these methods cannot profit from parallel computing power readily available on cloud platforms or do not provide exact samples and thus serve only specific use cases.

A peek under the hood

One of us (Simeon) used to do research in computational modeling of biomolecules, a field of research in which multimodality is a common issue.

That community often uses a specifically designed algorithm to deal with this problem, known as Replica Exchange or Parallel Tempering.

This algorithm runs multiple Markov chains in parallel that each sample increasingly “flatter” versions of a multimodal probability distribution and exchanges states between those chains.

If Replica Exchange is well configured, these exchanges help the Markov chain sampling the original distribution to escape from modes.

But several facts can make Replica Exchange hard to use:

- it is not implemented in some of the most popular PPLs (Stan, PyMC3),

- for difficult sampling problems, it requires parallel computing resources,

- its most important parameter (which determines “flatness”) can be hard to tune.

Chainsail implements Replica Exchange on a cloud platform and aims to alleviate these problems. While we postpone discussing the details for upcoming publications, in a nutshell, Chainsail relies on three key ideas:

- providing convenient interfaces to existing PPLs and for from-scratch definition of models,

- using cloud platforms to provide parallel computing power and exploit on-demand infrastructure for scaling up and down Chainsail runs dynamically,

- automatically tuning the most important parameter and otherwise improving sampling by using algorithms straight out of academic research

But all theory is grey, to quote the great German writer Goethe — let’s see how to actually use Chainsail.

Chainsail workflow using a toy example

Using Chainsail is easy. We now demonstrate these using the very simple example from above — a one-dimensional Gaussian mixture. Let’s find out how we can nicely sample this probability distribution with Chainsail!

-

Before you can use Chainsail, log in with your Google credentials on the Chainsail website and shoot us a quick email at [email protected] to get your account approved. This is required so we can prevent malicious activities and assure a fair use of the cloud computing resources Tweag provides.

-

On your machine, write a Python module

probability.pythat defines the probability distribution you want to sample. The interface for that is simple; all you have to specify is- a log-probability,

- the gradient of the log-probability,

- and an initial state.

We wrote a Python package

chainsail-helpersthat provides a definition of that interface and ready-to-use wrappers around PyMC3 and Stan models. But of course you can also code up your probability distribution from scratch, which we are going to do now. Theprobability.pyfor the above examples looks roughly as follows:import numpy import scipy from chainsail_helpers.pdf import PDF def log_gaussian(x, mu, sigma): '''Log-probability of a Gaussian distribution''' [...] class GaussianMixture(PDF): def __init__(self, means, sigmas, weights): # set attributes [...] def log_prob(self, x): return logsumexp( np.log(self.weights) + log_gaussian(x, self.means, self.sigmas)) def log_prob_gradient(self, x): [...] # this module has to export objects "pdf" and "initial_states" to work pdf = GaussianMixture(some_means, some_sigmas, some_weights) initial_states = np.array([1.0])For readability, this code is shortened, but the full code is available here.

-

Create a job on the Chainsail website: a. Upload a zip file with your probability distribution and possibly your data b. Set a few parameters a detailed explanation of which is available in the Chainsail resources repository. But for our purposes, the defaults will work just fine. c. Because

probability.pyusesnumpy,scipy, andchainsail_helpers, you have to include these dependencies in the corresponding field on the job creation form. -

Start your job on the job overview page. Through a couple of preliminary runs, Chainsail will perform automatic parameter tuning before a final production run is performed.

-

Once your job has completed successfully, download all samples via the button on the job dashboard or the job overview page. You then likely want to concatenate the sample batches using the

concatenate-sampleshelper script we provide in thechainsail-helperspackage:

$ unzip ~/Downloads/results.zip

$ python3 -m venv .venv

$ source .venv/bin/activate

$ pip install chainsail-helpers

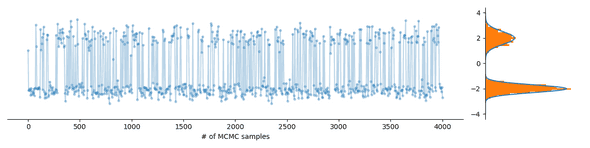

$ concatenate-samples production_run chainsail_samples.npyNow that we have obtained, in chainsail_samples.npy, a nice set of Chainsail samples, let’s check whether sampling is indeed better:

Seems like that worked nicely! We hope this walkthrough gave you a good idea of the Chainsail workflow and usage.

Current limitations

Making an early version of Chainsail available to the community is a way for us to gauge whether our efforts fulfil a genuine need. It also helps us inform where to take Chainsail development next so as to maximize its usefulness. But this also means that Chainsail users currently should expect to stumble upon bugs and glitches and that functionality of Chainsail is currently limited. More specifically, main drawbacks of the Chainsail version at the time of this writing are:

- a very minimal Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) implementation without mass matrix and trajectory length adaptation. Only the integration time steps currently undergo adaptation, with an extremely simple heuristic that yields acceptance rates of around 50%. The number of integration steps per HMC proposal is fixed to 20.

- sampling from models defined in Stan is very, very slow. But hey, it works!

- while Chainsail has many, many knobs to adjust, a large majority of these parameters cannot be set from the user interface yet.

Yes, yes, yes, we know, all that doesn’t make a tool well-adapted to each and every use case, but we hope it suffices to demonstrate the ideas and the potential of Chainsail and to pique your interest.

Feedback, please!

Given corresponding feedback by potential users, Tweag will likely be happy to invest further in Chainsail development, turning it into a useful tool for a broad range of users. And while Chainsail for now is closed source, given sufficient interest from the community, there is a good chance we will polish up source code and (most importantly) documentation a bit and finally make at least parts of Chainsail open source soon. So please do let us know whether you think a service such as Chainsail could potentially be useful for you — if this early version doesn’t do the trick for your specific problem, let us know how it could! The Chainsail team can be contacted on Twitter via Tweag’s handle (@tweagio) or directly via email at [email protected]. Also, don’t hesitate to open issues in the Chainsail resources repository.

Conclusion

We hope that this blog post gave you a good idea of what Chainsail is capable of and might be able to achieve in the future. Replica Exchange as an algorithm to enable sampling of multimodal distributions is not widely known in the probabilistic programming / Bayesian statistics community, but we believe that Chainsail has the potential to make this powerful method available and useful to a wider range of users. We rely on readers such as you and users of this early Chainsail version to confirm this assumption and steer future development efforts, so please get in touch and let us know what you think!

For readers who are interested in a real-world demonstration of Chainsail, we published a detailed blog post demonstrating how Chainsail helps to correctly analyze data using a soft k-means model. If you are interested in more details about the algorithms at work in Chainsail, or in additional documentation, our additional resources repository is what you are looking for.

Acknowledgements

The Chainsail team would like to explicitly thank the academic mentor of one of us (Simeon). Prof. Michael Habeck (University of Jena / Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences, Germany) introduced Simeon to many of the ideas and concepts that this project is based on. Most importantly, the automatic temperature schedule optimization is based on Prof. Habeck’s work. He is also looking for post-doc and PhD students interested in applications of Bayesian statistics in computational biology!

Behind the scenes

Simeon is a theoretical physicist who has undergone several transformations. A journey through Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, computational structural biology, a wet lab and renowned research institutions in Germany, Paris and New York finally led him back to Paris and to Tweag, where he is currently leading projects for a major pharma company. During pre-meeting smalltalk, ask him about rock climbing, Argentinian tango or playing the piano!

Guillaume is a versatile engineer based in Paris, with fluency in machine learning, data engineering, web development and functional programming.

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.