When GHC 9.2 was released in late 2021, I was eager to migrate my projects, particularly to reap the ergonomic benefits of the record dot syntax feature. My disappointment was immeasurable as I discovered that some of my more involved type-level computations caused GHCi to get stuck, just spinning indefinitely at full CPU load – it meant that in order to get productive with the new compiler, I would have to invest a potentially significant amount of time to debug a regression. Since my plate was already full at the time, I postponed this with the hope of an upcoming minor release magically fixing the issue.

At the beginning of May, I was presented with the opportunity to work on an arbitrary GHC topic in order to gain expertise as part of Tweag’s mission to improve GHC. To avoid having to select one of the many issues on the GHC bug tracker, I chose to investigate the aforementioned regression, getting the additional benefit of solving my immediate problem. This article is an account of my journey into the unknown, describing my approach at setting up the development environment for GHC, and following the obscure clues to identify and eliminate the root cause of this issue.

Investigate

When the only symptom of a problem is that nothing happens, finding a way to start debugging can be difficult. A good feedback loop would be to load the code with a GHC compiled from a local source tree, to allow me to add debug print statements to the compiler’s code, use profiling features and make changes to its behaviour to observe their impact.

For this method to be feasible, a few prerequisites have to be satisfied:

- The code has to be small enough for debug information not to be overwhelming

- The code should not have any library dependencies so it can be compiled with a GHC built from source without additional complex setup

- There needs to be an indication of roughly where to look in the large GHC codebase

- I have to be able to build GHC

The last condition, while obvious enough, poses a substantial obstacle to many people, since a project like GHC is incredibly complex, with decades-old legacy build infrastructure that may be fragile and hard to understand. Luckily, GHC’s build has made great strides with Hadrian, its custom build system, and users can rely on Nix to quickly spin up an environment that satisfies the build’s requirements.

Equipped with these tools, I was able to build a compiler using this sequence of commands (it required a bit of tweaking but it comes down to this):

nix-shell /path/to/ghc.nix --pure --arg withHadrianDeps true --arg withIde true

./boot

./configure $CONFIGURE_ARGS

hadrian/build stage2:exe:ghc-binIn order to facilitate fast recompilation after making small changes to GHC’s code, the build offers a mechanism to skip the bootstrapping sequence that would cause a rebuild to take significantly longer, limiting it to the second stage:

hadrian/build --freeze1 stage2:exe:ghc-binThe option --arg withIde is also crucial for development speed – it installs the

Haskell Language Server, greatly reducing the feedback time

when making changes to GHC code.

This setup is a solid basis for hacking on GHC, but in order to investigate the issue, the problematic code still has to be reduced and distilled to its bug-inducing essence. Since the issue popped up at an arbitrary location in a potentially large module with many dependencies this can be an arduous and frustrating process - like taking a big block of marble and chipping away anything that doesn’t look like David - but there is a fairly reliable path towards the goal:

1. Remove top level code in a bisecting fashion until the minimal expression causing the bug is identified

In a module containing tens of functions, the culprit is likely a single one of them, or a set of functions using a similar pattern. By removing one after another, GHC will eventually be able to succeed in compiling the module, revealing the offender. To speed this process up, it is useful to simply remove one half of the file and repeat the process with the half that still exhibits the bug (leaving in the parts that are needed by what remains).

After I started this process, I quickly realized a circumstance that changed the perception of the situation – I simply hadn’t waited long enough to see that what happened wasn’t, in fact, an infinite loop, but that it just took several minutes to compile this module that used to be processed within ten seconds, leading to the first key insight:

I am dealing with a substantial performance regression.

The performance aspect gave me another flash of inspiration:

I’ve only looked at this in GHCi, since that’s my usual workflow.

Might native code generation with optimizations enabled yield a better result?

A quick run of nix build revealed the second key insight:

The bug is specific to GHCi.

While this new information certainly foreshadows potential avenues for unearthing the root of the issue, the code still needs to be freed of package dependencies and complex types to allow debugging it efficiently in the GHC codebase. After all irrelevant parts have been stripped from the module, we’ll continue with the next step.

2. Replace complex types and expressions with dummies

Switching out types with simpler variants like () or '[] (and expressions with undefined) in random locations

allows the code to be reduced further, and even avoids the need for the next step for the irrelevant parts.

In this stage, a new problem surfaces that is especially pronounced in the case of a bug that is quantified by compile time: Every removal of complexity will cause a reduction in compile time, whether it is relevant for the bug or not. As the reproducer approaches minimality, it becomes increasingly difficult to discern the category in which a reduction falls.

3. Inline all imported types and functions

Inlining takes care of liberating the reproducer from library and module dependencies, with the unfortunate consequence of blowing the module back up to a considerable size. Depending on the magnitude of the involved dependencies, this needs to be interleaved with the other steps. After the definitions from a direct dependency have been relocated to the test case, transitive dependency imports have to be moved as well. If those were to be inlined recursively in one pass, the code may become unwieldy, so stripping each layer individually is sensible.

It is advisable to keep good track of the history of changes (for example using git), and to compare the current state

to an environment in which the bug is known not to occur, like GHC 9.0 in this scenario.

The potential for losing the trail during this process is high, and I had to backtrack a few times before arriving at

the final, basically irreducible, code that presented the undesirable symptoms in a measurable fashion.

The concrete code isn’t particularly illuminating, but I’ll provide it for anyone who’s interested:

type M = 5

type N = 5

type family Replicate (n :: Nat) (m :: Nat) :: [Nat] where

Replicate _ 0 = '[]

Replicate n m = n ': Replicate n (m - 1)

type family Next (n :: Nat) :: [Nat] where

Next 0 = '[]

Next n = Replicate (n - 1) M

data Result = Result [Result]

class Nodes (next :: [Nat]) (results :: [Result]) | next -> results

instance Nodes '[] '[]

instance (Tree n result, Nodes next results) => Nodes (n ': next) (result ': results)

class Tree (d :: Nat) (result :: Result) | d -> result

instance Nodes (Next n) result => Tree n ('Result result)

bug ::

Tree N res1 =>

Int

bug =

5

{-# noinline bug #-}

main ::

() ~ () =>

IO Int

main =

pure bugSome elements of this construction are not strictly part of the bug (or even seem nonsensical, like the () ~ ()

constraint); they are merely necessary to trigger the behaviour in a test case, since GHC might decide to simply skip

fully evaluating code paths that don’t produce anything that is actually used.

At the heart of the code lies a pair of mutually recursive classes, Tree and Nodes, that are traversed N times.

They were buried in some very convoluted generic derivation

mechanism that was

included in the app in which the problem occurred via several layers of dependencies, with the entirety of the involved code

spanning a few thousand lines.

Into the abyss

At this point, there was no further insight to be gained from manipulating the test case; the time had come to turn on

the head lamps and venture into the belly of the beast.

I grabbed my colleague Georgi Lyubenov and turned on the tracing flags, starting with -ddump-tc-trace for the type

checker, sifting through the thousands of lines of output that GHC produces with them, and matching them to GHC code in

the hopes of noticing a glaringly obvious culprit, which naturally didn’t reveal itself.

We needed a more principled approach, and since the measure of the problem was compile time, profiling seemed to be

a viable avenue.

Profiling the compiler

While profiling isn’t a trivial task in the general case of regular programs, applying it to the compiler itself requires even more effort. So far we had been building GHC with the default settings, which are optimized for speedy rebuilds, but have only few optimizations enabled – a factor that might obscure the information we were attempting to reveal.

Hadrian has a configuration option called “flavour” that determines, among other things, the optimization settings. These may be combined with “flavour transformers”, which allowed us to create a profiled compiler with strong optimization by running:

hadrian/build --flavour 'perf+profiled_ghc' stage2:exe:ghc-binAs a point of reference, we decided it to be prudent to also build GHC 9.0 in the same manner, and then compare the profiling output side by side until we encountered a large flashing sign indicating where the complexity diverged. Little did we know that the concept of flavour transformers was introduced only in GHC 9.2, leaving us no obvious way to achieve that goal!

Luckily, Hadrian’s code is quite accessible, and after a crash course from our colleague Alexis King, we were able to

jury-rig the 9.0 Hadrian to build an equivalent of the perf+profiled_ghc flavour.

With these additions to the tool belt, GHC produces a file named ghc.prof that contains the time and memory allocation

for each call frame.

There are plenty of tools that provide an interface for browsing profiling reports comfortably. We chose

profiteur, which outputs an HTML page in which you can click through

the call graph, where each frame is represented by a square whose size is proportional to the time spent within it.

Navigating our way through the data with 9.2 and 9.0 side-by-side, we arrived at a noticeably differing frame that

revealed the target of our exploration.

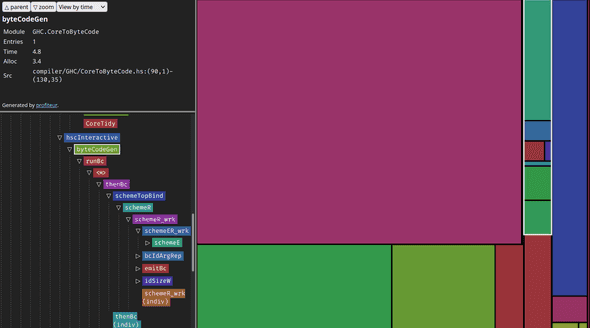

With 9.0, byteCodeGen used 4.8% of the total time:

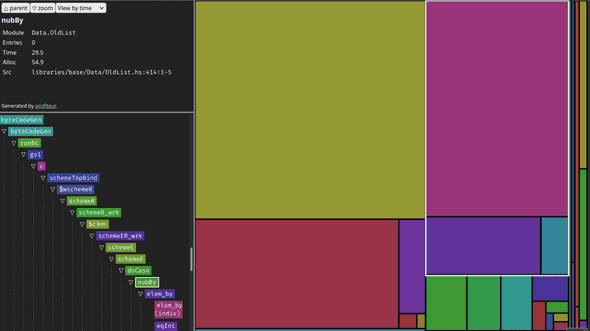

With 9.2, 29.5% of the total time was spent in one function inside byteCodeGen:

The delinquent was the function nub,

a specimen of considerable notoriety for its complexity of O(n2), which removes duplicates from a list.

Its call site was the file StgToByteCode.hs, responsible for generating the executable bytecode that powers GHCi,

which answers the question of why this didn’t happen with native compilation – it is a separate code generation

pipeline.

Replacing nub with a Set-based alternative (Set.toList . Set.fromList) reduced the compile time for our test case

from about 10 minutes to 1.5 minutes and made for a tiny

patch.

Conclusion

nub was introduced to this code in 2012, so why did it only now cause a noticeable performance impact?

Before GHC 9.2, bytecode was generated directly from a program’s representation in the intermediate language Core.

The insertion of an additional STG stage caused changes in that representation, with our test case resulting in

a data structure that accumulates thousands of entries in a list.

Presumably, the nub call had only ever operated on very small lists over the last decade, so its complexity hadn’t

been a significant factor.

A lesson one might take away from these insights is that it can always be dangerous to use quadratic combinators in the

face of a changing complex environment, despite the apparent initial certainty that there will be no arbitrarily large

inputs.

The GHC codebase still contains 16 uses of nub and 6 uses of nubBy in the compiler/ directory.

Are those more regressions waiting to happen?

Too bad we don’t encode complexity in types.

For a final insight, further research revealed that the list passed to nub isn’t just large – it is also quite stable

between iterations, causing substantial redundant overhead.

As an additional exercise, I attempted to devise an implementation that incrementally updates the final data structure

instead of regenerating it from the original list in every step, with quite satisfying

results.

Behind the scenes

Torsten is a Haskell architect with a passion for creating complex tools and libraries with cutting-edge technologies, seamless user experience, and detailed, accessible documentation.

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.