This guide explains how to install NixOS on a computer, with a twist.

If you use the same computer in different contexts, let’s say for work and for your private life, you may wish to install two different operating systems to protect your private life data from mistakes or hacks from your work. For instance a cryptolocker you got from a compromised work email won’t lock out your family photos.

But then you have two different operating systems to manage, and you may consider that it’s not worth the effort and simply use the same operating system for your private life and for work, at the cost of the security you desired.

I offer you a third alternative, a single NixOS managing two securely separated contexts. You choose your context at boot time, and you can configure both context from either of them.

You can safely use the same machine at work with your home directory and confidential documents, and you can get into your personal context with your private data by doing a reboot. Compared to a dual boot system, you have the benefits of a single system to manage and no duplicated package.

For this guide, you need a system either physical or virtual that is supported by NixOS, and some knowledge like using a command line. You don’t necessarily need to understand all the commands. The system disk will be erased during the process.

You can find an example of NixOS configuration files to help you understand the structure of the setup on this GitHub repository.

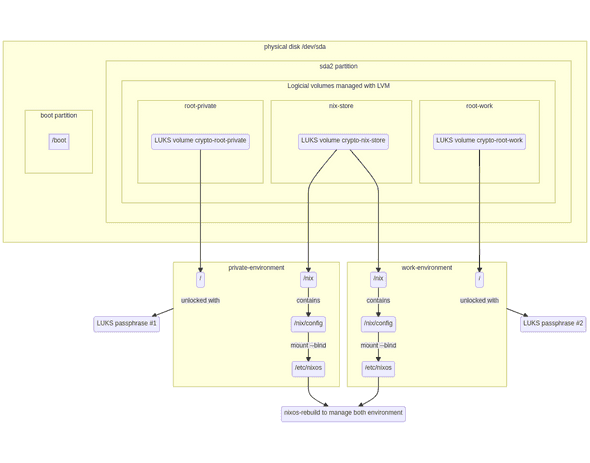

Disks

Here is a diagram showing the whole setup and the partitioning.

Partitioning

We will create a 512 MB space for the /boot partition that will contain the kernels, and allocate the space left for an LVM partition we can split later.

parted /dev/sda -- mklabel gpt

parted /dev/sda -- mkpart ESP fat32 1MiB 512MiB

parted /dev/sda -- mkpart primary 512MiB 100%

parted /dev/sda -- set 1 esp onNote that these instructions are valid for UEFI systems, for older systems you can refer to the NixOS manual to create a MBR partition.

In the NixOS Manual you can find documentation with regard to disks and partitioning.

Create LVM volumes

We will use LVM so we need to initialize the partition and create a Volume Group with all the free space.

pvcreate /dev/sda2

vgcreate pool /dev/sda2We will then create three logical volumes, one for the store and two for our environments:

lvcreate -L 15G -n root-private pool

lvcreate -L 15G -n root-work pool

lvcreate -l 100%FREE -n nix-store poolNOTE: The sizes to assign to each volume is up to you, the nix store should have at least 30GB for a system with graphical sessions. LVM allows you to keep free space in your volume group so you can increase your volumes size later when needed.

Encryption

We will enable encryption for the three volumes, but we want the nix-store partition to be unlockable with either of the keys used for the two root partitions. This way, you don’t have to type two passphrases at boot.

cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/pool/root-work

cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/pool/root-private

cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/pool/nix-store # same password as work

cryptsetup luksAddKey /dev/pool/nix-store # same password as privateWe unlock our partitions to be able to format and mount them. Which passphrase is used to unlock the nix-store doesn’t matter.

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/pool/root-work crypto-work

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/pool/root-private crypto-private

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/pool/nix-store nix-storePlease note we don’t encrypt the boot partition, which is the default on most encrypted Linux setup. While this could be achieved, this adds complexity that I don’t want to cover in this guide.

Note: the nix-store partition isn’t called crypto-nix-store because we

want the nix-store partition to be unlocked after the root partition to

reuse the password. The code generating the ramdisk takes the unlocked

partitions’ names in alphabetical order, by removing the prefix crypto

the partition will always be after the root partitions.

Formatting

We format each partition using ext4, a performant file-system which doesn’t require maintenance. You can use other filesystems, like xfs or btrfs, if you need features specific to them.

mkfs.ext4 /dev/mapper/crypto-work

mkfs.ext4 /dev/mapper/crypto-private

mkfs.ext4 /dev/mapper/nix-storeThe boot partition

The boot partition should be formatted using fat32 when using UEFI with

mkfs.fat -F 32 /dev/sda1. It can be formatted in ext4 if you are using

legacy boot (MBR).

Preparing the system

Mount the partitions onto /mnt and its subdirectories to prepare for

the installer.

mount /dev/mapper/crypto-work /mnt

mkdir -p /mnt/etc/nixos /mnt/boot /mnt/nix

mount /dev/mapper/nix-store /mnt/nix

mkdir /mnt/nix/config

mount --bind /mnt/nix/config /mnt/etc/nixos

mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/bootWe generate a configuration file:

nixos-generate-config --root /mntEdit /mnt/etc/nixos/hardware-configuration.nix to change the following parts:

fileSystems."/" =

{ device = "/dev/disk/by-uuid/xxxxxxx-something";

fsType = "ext4";

};

boot.initrd.luks.devices."crypto-work".device = "/dev/disk/by-uuid/xxxxxx-something";by

fileSystems."/" =

{ device = "/dev/mapper/crypto-work";

fsType = "ext4";

};

boot.initrd.luks.devices."crypto-work".device = "/dev/pool/root-work";We need two configuration files to describe our two environments, we will

use hardware-configuration.nix as a template and apply changes to it.

sed '/imports =/,+3d' /mnt/etc/nixos/hardware-configuration.nix > /mnt/etc/nixos/work.nix

sed '/imports =/,+3d ; s/-work/-private/g' /mnt/etc/nixos/hardware-configuration.nix > /mnt/etc/nixos/private.nix

rm /mnt/etc/nixos/hardware-configuration.nixEdit /mnt/etc/nixos/configuration.nix to make the imports code at

the top of the file look like this:

imports =

[

./work.nix

./private.nix

];Remember we removed the file /mnt/etc/nixos/hardware-configuration.nix

so it shouldn’t be imported anymore.

Now we need to hook each configuration to become a different boot entry, using the NixOS feature called specialisation. We will make the environment you want to be the default in the boot entry as a non-specialised environment and non-inherited so it’s not picked up by the other, and a specialisation for the other environment.

For the hardware configuration files, we need to wrap them with some code to create a specialisation, and the “non-specialisation” case that won’t propagate to the other specialisations.

Starting from a file looking like this, some code must be added at the top and bottom of the files depending on if you want it to be the default context or not.

Content of an example file:

{ config, pkgs, modulesPath, ... }:

{

boot.initrd.availableKernelModules = ["ata_generic" "uhci_hcd" "ehci_pci" "ahci" "usb_storage" "sd_mod"];

boot.initrd.kernelModules = ["dm-snapshot"];

boot.kernelModules = ["kvm-intel"];

boot.extraModulePackages = [];

fileSystems."/" = {

device = "/dev/mapper/crypto-private";

fsType = "ext4";

};

---8<-----

[more code here]

---8<-----

swapDevices = [];

networking.useDHCP = lib.mkDefault true;

hardware.cpu.intel.updateMicrocode = lib.mkDefault config.hardware.enableRedistributableFirmware;

}Example result of the default context (See on GitHub):

({ lib, config, pkgs, ...}: {

config = lib.mkIf (config.specialisation != {}) {

boot.initrd.availableKernelModules = ["ata_generic" "uhci_hcd" "ehci_pci" "ahci" "usb_storage" "sd_mod"];

boot.initrd.kernelModules = ["dm-snapshot"];

boot.kernelModules = ["kvm-intel"];

boot.extraModulePackages = [];

fileSystems."/" = {

device = "/dev/mapper/crypto-private";

fsType = "ext4";

};

---8<-----

[more code here]

---8<-----

swapDevices = [];

networking.useDHCP = lib.mkDefault true;

hardware.cpu.intel.updateMicrocode = lib.mkDefault config.hardware.enableRedistributableFirmware;

};

})Note the extra leading ( character that must also be added at the

very beginning.

Example result for a specialisation named work (See on GitHub):

{ config, lib, pkgs, modulesPath, ... }:

{

specialisation = {

work.configuration = {

system.nixos.tags = [ "work" ];

boot.initrd.availableKernelModules = ["ata_generic" "uhci_hcd" "ehci_pci" "ahci" "usb_storage" "sd_mod"];

boot.initrd.kernelModules = ["dm-snapshot"];

boot.kernelModules = ["kvm-intel"];

boot.extraModulePackages = [];

fileSystems."/" = {

device = "/dev/mapper/crypto-work";

fsType = "ext4";

};

---8<-----

[more code here]

---8<-----

swapDevices = [];

networking.useDHCP = lib.mkDefault true;

hardware.cpu.intel.updateMicrocode = lib.mkDefault config.hardware.enableRedistributableFirmware;

};

};

}System configuration

It’s now the time to configure your system as you want. The file

/mnt/etc/nixos/configuration.nix contains shared configuration, this

is the right place to define your user, shared packages, network and services.

The files /mnt/etc/nixos/private.nix and /mnt/etc/nixos/work.nix

can be used to define context specific configuration.

LVM Workaround

During the numerous installation tests I’ve made to validate this guide, on some hardware I noticed an issue with LVM detection, add this line to your global configuration file to be sure your disks will be detected at boot.

boot.initrd.preLVMCommands = "lvm vgchange -ay";Installation

First installation

The partitions are mounted and you configured your system as you want it, we can run the NixOS installer.

nixos-installWait for the copy process to complete after which you will be prompted for the root password of the current crypto-work environment (or the one you mounted here), you also need to define the password for your user now by chrooting into your NixOS system.

## nixos-enter --root /mnt -c "passwd your_user"

New password:

Retape new password:

passwd: password updated successfully

## umount -R /mntFrom now, you have a password set for root and your user for the crypto-work environment, but no password are defined in the crypto-private environment.

Second installation

We will rerun the installation process with the other environment mounted:

mount /dev/mapper/crypto-private /mnt

mkdir -p /mnt/etc/nixos /mnt/boot /mnt/nix

mount /dev/mapper/nix-store /mnt/nix

mount --bind /mnt/nix/config /mnt/etc/nixos

mount /dev/sda1 /mnt/bootAs the NixOS configuration is already done and is shared between the two

environments, just run nixos-install, wait for the root password to

be prompted, apply the same chroot sequence to set a password to your

user in this environment.

You can reboot, you will have a default boot entry for the default chosen environment, and the other environment boot entry, both requiring their own passphrase to be used.

Now, you can apply changes to your NixOS system using nixos-rebuild

from both work and private environments.

Conclusion

Congratulations for going through this long installation process. You

can now log in to your two contexts and use them independently, and you can

configure them by applying changes to the corresponding files in /etc/nixos/.

Going further

Swap and hibernation

With this setup, I chose to not cover swap space because this would allow to leak secrets between the contexts. If you need some swap, you will have to create a file on the root partition of your current context, and add the according code to the context filesystems.

If you want to use hibernation in which the system stops after dumping its memory into the swap file, your swap size must be larger than the memory available on the system.

It’s possible to have a single swap for both contexts by using a random encryption at boot for the swap space, but this breaks hibernation as you can’t unlock the swap to resume the system.

Declare users’ passwords

As you noticed, you had to run passwd in both contexts to define your

user password and root’s password. It is possible to define their password

declaratively in the configuration file, refers to the documentation

ofusers.mutableUsers and users.extraUsers.<name>.initialHashedPassword

for more information.

Rescue the installation

If something is wrong when you boot the first time, you can reuse the

installer to make changes to your installation: you can run again the

cryptsetup luksOpen and mount commands to get access to your

filesystems, then you can edit your configuration files and run

nixos-install again.

Behind the scenes

Solène dedicates most of her time contributing to libre software and experimenting with new ideas, publishing results on her blog. She is working at Tweag as a Developer Productivity Software Engineer, leveraging lessons from her experiments to help developers in their daily tasks.

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.